The London Necropolis Railway

Hello again! So glad you could join me in my newsletter. Please, pull up a chair next to the fire. Yes, that's it. Would you like some cocoa? There, now you can get all warmed up––you're dripping wet! How's the work been going this week? I see, well that's certainly something. And the family? Mm-hm, just like them isn't it? Oh don't mind old Kashtanka there, he loves a good scratch behind the ears. How have I been, you ask? Well…

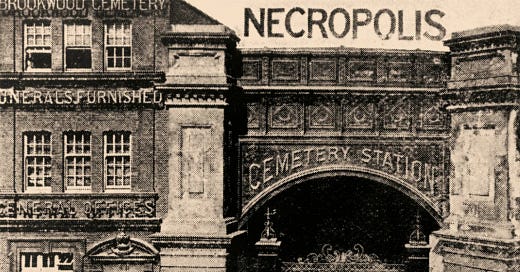

I Read About The Way Many Londoners Took Their Final Departure

For nearly 100 years, Cemetery Station served as the terminus of the London Necropolis Railway, a Victorian solution to that most pressing of Victorian problems: hygiene. Having more than doubled its population in the first half of the 19th century, by 1850 London was running out of room for its deceased. As traditional parish churchyards struggled to inter the masses of London’s dead, bodies were regularly exhumed to make room for more. As National Geographic writes: “Graves were dug too shallow, and too close together. Hard rains exposed grim scenes of decomposition.” Worse, decaying corpses contaminated the water supply, and the city was victim to regular outbreaks of cholera, smallpox, measles, and typhoid fever.

In 1851, the Burials Act finally prohibited new burials in the “built-up” parts of London. Though the so-called “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries, built in the 1830s, provided grounds on the outskirts of the city as a burial option, access to their beautiful park-like gardens came at a premium beyond the means of the average Londoner. The problem, then, seemed only to be getting worse, with no viable solution for the great majority of the population.

Enter two entrepreneurs, Richard Broun and Richard Sprye, who planned an enormous, 500-acre gravesite 23 miles southwest of London. The cemetery would be the largest ever built: large enough, they claimed, to house the remains of all Londoners into perpetuity. The cemetery was designed in imitation of the Magnificent Seven, with tranquil park-like grounds boasting beautiful landscaping (and even the occasional American Redwood). Bodies and mourners alike would be transported via a new and economical train line, so that, through technological innovation and sheer Victorian ingenuity, the twin problems of cost and space could both be solved in one fell swoop. The Brookwood Cemetery, as it was called, officially opened in 1854, and along with it was inaugurated the means of conveyance for visitors and future residents alike: the London Necropolis Railway.

National Geographic describes the typical Brookwood funeral thus:

The coffin was hauled from the place of death (typically via a short horse-drawn hearse ride) and loaded into the shared storage vault beneath the arched entryway of the company’s private terminus at London’s Waterloo Station. Funeral parties gathered in the morning, dressed in black and perhaps clutching their invitations that bore the name of the deceased alongside the train’s departure and return times. Bodies were loaded into dedicated railcars. Mourners bought their discounted rail tickets and stepped into separate passenger cars. Each morning, the funeral train would depart Waterloo, make its solemn journey to the cemetery, and return in the afternoon.

The deceased’s religion determined where their final journey would end. Once inside the cemetery, the train chugged into two stations: one for members of the Church of England and the other for “nonconformists.” The cemetery station buildings often served as the waiting room, the funeral reception area, the living quarters for cemetery employees, and, strategically, the showroom where visitors could peruse an assortment of made-on-site headstones.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom in these stations. They also housed their own pubs. (It’s unclear if the signs declaring “Spirits served here” were intended to be a point of levity.) The daughter of one of the cemetery’s staff recalled, years later: “In addition to catering for mourners, who mostly came down from London by train, we also had local people who walked through the cemetery calling in for afternoon tea. Of course the bar was an added attraction, as it had a full license and kept to pub opening hours, much to the delight of the locals.”

Though never as popular as envisioned, the Necropolis Railway kept chugging along (as it were) for a surprisingly long time, until 1941, when the Waterloo Station was bombed. The cemetery itself, however, continues on, though in a much more limited capacity.

For far more detail than is found in either the National Geographic or Wikipedia articles, see here.

I Learned Why So Many Pigeons Have Deformed Toes

It’s us. I guess I sort of assumed it was probably us, but I never would’ve guessed the precise mechanism. Apparently our human hair, of all things, gets wrapped around their digits and just never lets go. Poor things.

I Stumbled Across A Little-Known Rap Battle in Huck Finn

It’s part of the so-called “raft episode,” which was excised from the manuscript before publication in order to make the book shorter, so even if you’ve read Huckleberry Finn before, it’s unlikely you’ve read this part.

While floating down the river, Huck comes upon a huge raft that houses multiple tents and an entire encampment of men, most of whom are just then drunkenly chatting and singing around a central fire. One man, however, gets a little carried away with his singing, to the annoyance of everyone else. When he refuses to quiet down, Huck watches in hiding as the other men accost him:

They was all about to make a break for him, but the biggest man there jumped up and says:

“Set whar you are, gentlemen. Leave him to me; he’s my meat.”

Then he jumped up in the air three times, and cracked his heels together every time. He flung off a buckskin coat that was all hung with fringes, and says, “You lay thar tell the chawin-up’s done”; and flung his hat down, which was all over ribbons, and says, “You lay thar tell his sufferin’s is over.”

Then he jumped up in the air and cracked his heels together again, and shouted out:

“Whoo-oop! I’m the old original iron-jawed, brass-mounted, copper-bellied corpse-maker from the wilds of Arkansaw! Look at me! I’m the man they call Sudden Death and General Desolation! Sired by a hurricane, dam’d by an earthquake, half-brother to the cholera, nearly related to the smallpox on the mother’s side! Look at me! I take nineteen alligators and a bar’l of whisky for breakfast when I’m in robust health, and a bushel of rattlesnakes and a dead body when I’m ailing. I split the everlasting rocks with my glance, and I squench the thunder when I speak! Whoo-oop! Stand back and give me room according to my strength! Blood’s my natural drink, and the wails of the dying is music to my ear. Cast your eye on me, gentleman! and lay low and hold your breath, for I’m ‘bout to turn myself loose!”

All the time he was getting this off, he was shaking his head and looking fierce, and kind of swelling around in a little circle, tucking up his wristbands, and now and then straightening up and beating his breast with his fist, saying “Look at me, gentlemen!” When he got through, he jumped up and cracked his heels together three times, and let off a roaring “Whoo-oop! I’m the bloodiest son of a wildcat that lives!”

Then the man that had started the row tilted his old slouch hat down over his right eye; then he bent stooping forward, with his back sagged and his south end sticking out far, and his fists a-shoving out and drawing in in front of him, and so went around in a little circle about three times, swelling himself up and breathing hard. Then he straightened, and jumped up and cracked his heels together three times before he lit again (that made them cheer), and he began to shout like this:

“Whoo-oop! bow your neck and spread, for the kingdom of sorrow’s a-coming! Hold me down to the earth, for I feel my powers a-working! whoo-oop! I’m a child of sin, don’t let me get a start! Smoked glass, here, for all! Don’t attempt to look at me with the naked eye, gentlemen! When I’m playful I use the meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude for a seine, and drag the Atlantic Ocean for whales! I scratch my head with the lightning and purr myself to sleep with the thunder! When I’m cold, I bile the Gulf of Mexico and bathe in it; when I’m hot I fan myself with an equinoctial storm; when I’m thirsty I reach up and suck a cloud dry like a sponge; when I range the earth hungry, famine follows in my tracks! Whoo-oop! Bow your neck and spread! I put my hand on the sun’s face and make it night in the earth; I bite a piece out of the moon and hurry the seasons; I shake myself and crumble the mountains! Contemplate me through leather––don’t use the eye! I’m the man with a petrified heart and biler-iron bowels! The massacre of isolated communities is the pastime of my idle moments, the destruction of nationalities the serious business of my life! The boundless vastness of the great American desert is my inclosed property, and I bury my dead on my own premises!” He jumped up and cracked his heels together three times before he lit (they cheered him again), and as he come down he shouted out: “Whoo-oop! bow your neck and spread, for the Pet Child of Calamity’s a-coming!”

Then the other one went to swelling around and blowing again––the first one––the one they called Bob; next, the Child of Calamity chipped in again, bigger than ever; then they both got at it at the same time, swelling round and round each other and punching their fists most into each other’s faces, and whooping and jawing…then Bob called the Child names, and the Child called him names back again; next, Bob called him a heap rougher names, and the Child come back at him with the very worst kind of language; next, Bob knocked the Child’s hat off, and the Child picked it up and kicked Bob’s ribbony hat about six foot; Bob went and got it and said never mind, this warn’t going to be the last of this thing, because he was a man that never forgot and never forgive, and so the Child better look out, for there was a time a-coming, just as sure as he was a living man, that he would have to answer to him with the best blood in his body. The Child said no man was willinger than he for that time to come, and he would give Bob fair warning, now, never to cross his path again, for he could never rest till he had waded in his bood, for such was his nature, though he was sparing him now on account of his family, if he had one.

Both of them was edging away in different directions, growling and shaking their heads and going on about what they was going to do; but a little black-whiskered chap skipped up and says:

“Come back here, you couple of chicken-livered cowards, and I’ll thrash the two of ye!”

And he done it, too.

For my money, it should’ve been left in.

And Finally…

Homeowners in the parched state of Arizona have begun painting their lawns green in an effort to save water and money. With any number of shades to choose from, The Wall Street Journal reports that the paint can make grass look like it belongs “on the fairways of St. Andrews.” At least one resident groused that the paint tinted his dog’s paws green.

That’s All for this Week

Thanks for asking! Same time next week? I’ll keep the kettle on.